-

Revised Galactica.TV 2009 interview: Marcel Damen & David Stipes

Posted on October 10th, 2022 No commentsPart 1 of 2009 interview. The original online Galactica.TV website postings appear to be lost. This article was recreated from transcriptions generated during the original interview between David Stipes and Marcel Damen. Minor editing was done for info corrections, clarity, and updates. Galactica.TV questions in boldface type are by Marcel Damen.

You started creating your own visual effects for movies at a young age. What brought this about? What movie made such an impression on you to get you involved in this field?

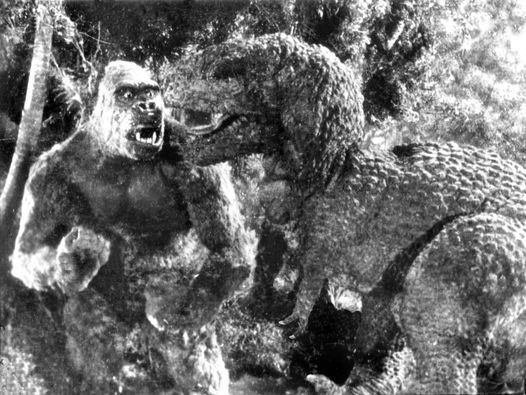

That’s pretty straightforward, King Kong and The Son of Kong. When I was in the third or fourth grade, the films were shown on television. I was amazed. I didn’t know what was going on exactly, but I knew something was. So I asked my mom, “How did they get King Kong to do all this stuff?” and she said, “Oh, David, it’s a trained chimpanzee.” Well, of course, they didn’t look or move like chimpanzees, and I thought, “That’s not right.” So even though I was very young, I knew something was going on, and it wasn’t what my mom said.

So it fascinated me. When I was about eleven, I discovered Famous Monsters of Filmland, Forrest J Ackerman’s magazine. Forry wrote about Willis O’Brien, King Kong, The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, and Ray Harryhausen. I thought, “Wow! This is terrific.”

I just started collecting everything I could on Kong and movie monsters. I was eagerly waiting for the magazines to come out because there was no internet, pro articles, books, absolutely nothing available. I absorbed these magazines and tried to figure out simple effects.

Eventually, there were many knockoffs of Famous Monsters of Filmland. Forry came out with Spacemen Magazine and Screen Thrills Illustrated. I read as many as I could. I began to see that many people worked on monster and fantasy movies.

Then in Famous Monsters of Filmland, there was a little blurb in the news column that said: “King Kong fan David Allen would love to meet or talk to anybody else who’s a King Kong fan.” Of course, David never said that, but Forry posted it for him. It turned out that David Allen lived just a few miles away.

I wrote to David and later called him. I was still so young that I couldn’t drive on my own. I was just getting a trainer’s permit. So my mom drove me to see David Allen, where he was involved with writing, artwork, and film tests. He was using the “Taurus Monster” that he had recently completed. Taurus was used later in Equinox.

I was fortunate to meet someone like David, who’s only a few years older than me and already doing what I wanted to do. I was excited.

David became my mentor for a long time — talking to me on the phone, looking at my drawings, and allowing me to visit. Eventually, I could drive myself to David’s house, and he let me help with a few shots. So I got to learn about sculpting, molds, and armatures. David encouraged me to build my first monster puppet. I did an armature and a sculpted model. Some of that work was crude, oh so crude, but I learned a lot by doing it. David was so encouraging and gracious about his time and his knowledge.

In many ways, David Allen set an excellent example for me to be generous with information to my students and people who have come to me over the years. Maybe even to my detriment at times, but overall I think it has been an excellent experience to share this and get a chance to have somebody like David in my life. He introduced me to Jim Danforth and Dennis Muren. When Dennis started doing his film, Equinox, he invited Jim Danforth and David Allen to be involved. David Allen then asked me to help. I was still in high school and got to build ‘Charlie,’ the corpse, a temple model, and an animation house David Allen destroyed in a stop-motion scene.

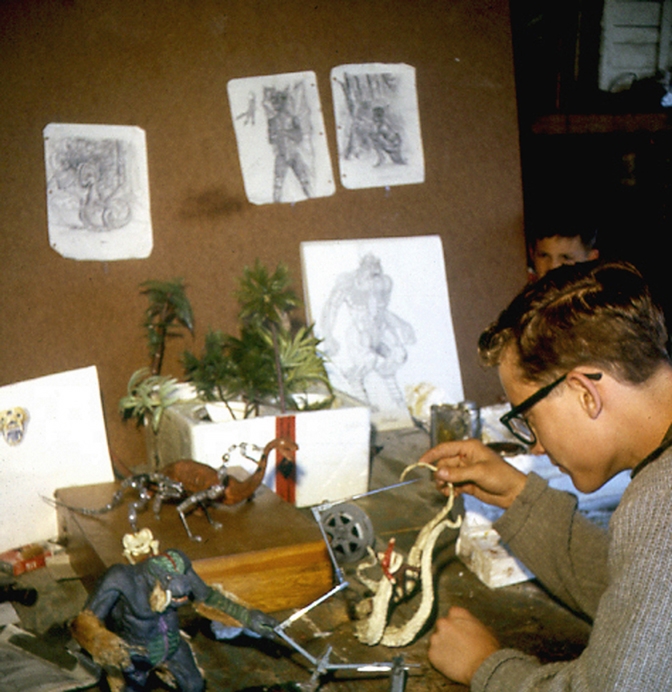

David Allen working on the tentacle creature for ‘Equinox’

I mean, how great was that? I visited Dennis Muren and saw him compositing with front projection several years before 2001: A Space Odyssey. I was in awe seeing all of this fantastic work that Dennis, David, and Jim were doing. It was a wonderful experience, and I was very blessed.

When did you know this was more than just a hobby and you wanted to make your career out of this?

Well, it was never just a hobby to me. It was sort of an obsession. I went to some high school activities, but whenever I could, I was out in my parent’s garage doing stop-motion animation or practicing matte painting. I’d build my own 16 mm aerial image projector and printer. I was always messing with techniques as I discovered them.

In parent’s garage circa 1965

As I saw VFX shots, I would go to my garage and try to replicate them or do something similar. Sometimes it worked; sometimes, it didn’t. Most of the results were pretty crude, but I kept learning. I was building on a knowledge base I’ve used all my life.

Were you supported by your parents in this choice?

The only significant support I received was when I was obnoxiously persistent that I wanted a movie camera. So, while I was in high school, they bought me an 8 mm camera, which was pretty much the limit of the support. I had researched and requested this funky 8 mm camera that could backwind, do double exposures, and shoot single frames. I was in heaven for a while.

Setting up a split-screen shot circa 1965

I did a split screen around our house and animated my stop-motion monster walking in, tearing the roof off, reaching in, and grabbing somebody. It was all done in 8 mm. They were amazed I could do this, although they thought it was silly and a waste of time.

Even after I began working professionally, because it wasn’t 100% consistent, my mom literally said, “When are you going to stop wasting time with this silly filmmaking and get a real job?” So even toward the end of their lives, after I had my pro studio, they’d drive close by on the freeway, visiting their friends, but they never came to see my studio.

You studied Art and Film both in college. Who were your mentors and examples during that period? Who did you look up to?

I never got the chance to study film. I wanted to go to USC or UCLA, which were so expensive. There were no scholarships I could get a hold of, and my parents couldn’t afford the tuition. So I just went to a Junior College and the State University and became an art major. Most people in the art department pushed me to declare myself as a major in abstract painting or commercial art. But, of course, I wasn’t interested in that. I wanted to do film and VFX work. So every chance I could, I would take independent studies where I could tailor my class to some aspect of filmmaking. I got a lot of resistance from the college people because I didn’t want to follow their standard curriculum. I took the necessary classes and did the best I could, but if it wasn’t about filmmaking, stop-motion animation, cartoon animation, drawing, and techniques like that, I wasn’t excited about it. So wherever I could, I’d take filming classes and history of film.

Since you started at this very young and already worked with some leading people in the industry at that time, like Dennis Muren, why did you ever bother to go through College and University in the first place? Why didn’t you simply continue in the industry itself?

Well, I was still pretty young. Going to college was expected at that time. You have to keep in mind that I graduated from high school in 1966. Everybody went to college, and I didn’t know enough in 1966 to get hired to do anything professionally.

About 1970, the folks at Cascade Pictures needed more stop-motion animators, so Jim Danforth and Phil Kellison, the effects supervisor, hired David Allen. I frequently visited David Allen at Cascade and got to see Jim Danforth. Then I got to know Phil Kellison, a more mature VFX artist.

Phil Kellison (c) vfxmasters.com by Harry Walton

Phil never took on the role of a mentor, like, “Hey buddy, let me take you under my wing” or anything. But I learned so much because I was at Cascade for a long time, working and watching Phil, Jim, and Dave. For that, I was so fortunate and grateful.

I got some great career advice from Phil Kellison: learn to do multiple things and not be fixated on just one thing. I took that advice to heart. I wound up doing many different jobs and skills in my career.

When I was teaching, I drew upon these varied, wild job experiences to share with students. My background was so diverse that I got to teach in Visual Effects, Digital Film, and Animation majors. I was equally qualified to be in all three of them.

What were the most important skills you learned when you just started?

I learned much from attending school and my jobs at Cascade. Yes, I was learning many technical skills, but I needed to know about working with people, not taking things personally, and how to stand up for myself. Many self-growth issues came to light that I needed to work on in my life and my personality. There were a lot of experiences that I considered very unpleasant. But, over the years, they have helped me become a more mellow person and realize what poor treatment felt like. They tempered me for when I later became a boss having my own company and employees.

Later, when I was an instructor, I was more conscious of how I interacted with people because of the, shall we say, unconscious way I was treated. People were just pretty oblivious to what they were saying and doing. And, in truth, I was sometimes somewhat unconscious, too. I said and did things that I immaturely thought were funny but wound up hurting people’s feelings. So yeah, I had to learn a lot to learn and apply. While I gained technical skills, the film industry was more about learning to be a better human being.

How did you get involved in Battlestar Galactica?

Dennis Muren had come to work at Cascade. I’d known him for a while because I’d worked on his Equinox film. At some point, he heard an assistant was needed to work on shots for this funky little film, Star Wars.

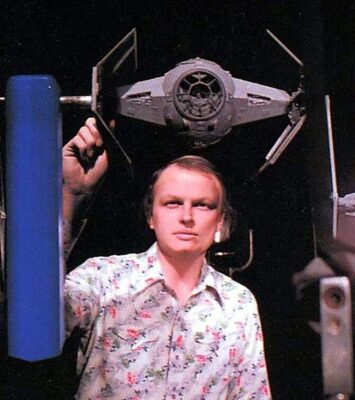

Dennis Muren

So Dennis interviewed with John Dykstra, who hired him to work with Richard Edlund on the night shift. So I went out there to visit Dennis and see his work. Wow! I walk into this fantastic motion control studio with electronically controlled cameras, stepper motor-driven things, models, and spaceships. I was amazed.

That opened my eyes because we were still in “boilerplate technology when I first started in VFX.” It was analog, pre-digital, pre-computer, and we didn’t even have videotape players when we started. So, for example, we would lay out 50 feet of paper tape, go down and draw 1/4-inch marks. We used a needle as our indicator and moved the dolly by hand for 50 feet at 1/4 inch per film frame to animate it. So that’s how we did it, over and over and over.

So when motion control came along, and Star Wars exposed me to that growth step, it was eye-opening, like when I first met David Allen and was exposed to stop-motion, optical printing, front and rear projection, and all those techniques. Wow! I wanted to do motion control, too! But, of course, the equipment was costly at that point, and I didn’t know how to do it.

Over the next couple of years, I kept pushing, trying to learn more and more about motion control and digital technology. So in the mid to late seventies, there was a break in writing about visual effects as American Cinematographer and Cinefantistique came out with articles about Star Wars. Then, about 1978, I think Starlog magazine had an article, “See what $2 million can buy,” with preview images from the new Battlestar Galactica show.

I heard they were hiring for Battlestar Galactica. So I went and interviewed with John Dykstra.

John Dykstra circa 1977-78

Unfortunately, I was very formal and stuffy. The contrast was pretty funny because John Dykstra was kicking back, smoking, and scratching his big dog. He appeared to be a hippie with a loose shirt, shorts, and sandals. He showed me around the studio, but he didn’t hire me.

I kept going along on commercials, and then Dykstra pulled out of Battlestar Galactica to work on something else. So Univeral shipped the equipment & resources over to their Hartland VFX facility.

Cascade Pictures closed in 1975, and a follow-up company called CPC Associates took its place. It incorporated many of the Cascade people, including David Allen and myself. Phil Kellison had gone on to another company. So now it was David Allen and a few others. There also was a matte painter named Jena Holman, who frequently worked with us. David later left CPC Associates and started on The Primeval, so I inherited the position of effects supervisor for CPC in 1978. Jena Holman was accepted into the matte painter union, and she started working over at Universal Hartland.

Jena Holman at Hartland circa 1978

Jena recommended that I come over because they needed a matte camera person to work with her. So I interviewed with Peter Anderson. Peter loved what I was doing and liked me. So finally, here was a chance for me to learn motion control. So I left CPC Associates and went to work at Universal Hartland towards the end of 1978.

The Hartland facility was working on Buck Rogers, the feature film, and they were also working on Battlestar Galactica. My primary duties were to support the matte work. In addition, I often went to locations and supervised the photography of background plates. I loved the whole matte painting process. I had experimented with it from the time I was in high school. Eventually, I did matte paintings for other feature films and taught it for a while. At that time, because it was very much union bound, I wasn’t officially allowed to do anything other than union-specified work.

At the studio, I did color testing, test composites, and whatever was needed for Jena to do the matte paintings. Because of my research in matte painting, testing, and talking with people, I knew how to do original negative matte painting compositing. So we did original negative and rear-projection matte painting composites and turned shots around pretty fast, which is what they desperately needed. The Hartland facility was producing 50-75 shots/week. They were just struggling to get shots done. They had over 100 people, and the work was all done analog / photo-chemical.

What were your favorite areas to work in?

When I wasn’t working on a matte camera, I’d be working on the motion control stage, or sometimes they’d let me help in the model shop or something.

I got the chance to learn some beginner motion control, but I didn’t do much of it. Because I had this weird, eclectic background, I was doing all of the odd shots using techniques that were not motion control. For example, I filmed a moving model reflection test with stop-motion animation because all the motion control setups were tied up. They were amazed I could do shots without the electronics. But, to be fair, that was their experience base. I did not have their experience in electronics, and they did not have my more hands-on approaches.

Can you remember the first thing you started working on?

I started by helping Jena Holman with her matte shots for Buck Rogers, such as the ‘New Chicago’ matte shot. I was shooting film tests and moving the heavy glass paintings. The glass plates were large in wood frames. Unfortunately, the frames were pine that began warping and cracking the glass. We researched and decided to use kiln-dried redwood for the frames. It solved the glass cracking problem but made the glass and frames larger and heavier.

I had a chance to do all kinds of funky stuff that drove the union people crazy because they wanted to put people into little niches.

I soon assisted with the Ship of Lights from the “War of the Gods” episode. I had a model-maker background, and though I wasn’t legally in the model-making union, I was allowed to help build this fun model.

How many people worked on the Ship of Lights? Can you remember that?

I know that artist Wendy Dupont worked on it with several model makers. Let’s see. I’m looking at Starlog #27 with a picture of Wendy on the cover. I don’t remember all the guys. I remember Wendy being the main driving force on it.

Was this the only model you worked on, or did you also work on other models?

If you look in Starlog #27, page 34, there’s one of the episodes where Starbuck and Apollo sneak on one of the Cylon Basestars. There’s a big miniature in there where they had the different Cylon ships parked in there. So I got a chance to work on that. The people at Hartland were fantastic, allowing me to work on a few projects like that.

Cylon Basestar interior model.

Most of the time, my job was to be a camera person. Again, it was a union shop, and they could only indulge in a little bit of rule-bending

You didn’t work on any of the Buck Rogers models?

The only model-related thing I did on Buck Rogers was in the Second Season when they introduced the Hawk ship. I did that shot with the Hawk ship, where the claws unfold and come out. I used stop-motion on that episode. They didn’t have the money or the time to build an extensive mechanical, so I made the little claws out of styrene pieces. I pinned them together, used some stick wax to hold position, and just animated these little claws coming out of the bottom of the ship. It was one of those weird little things I could do because of my varied background.

Can you remember some other weird little things you had to do for Battlestar Galactica?

Yeah, we did a gas planet. It was one of the things where Peter Anderson said: “We really need these planet shots, and we only got about three hours to do them in.”

They were supposed to be gas planets, which was a last-minute thing. How were we going to do this? We had no time to experiment, so we just did it based on our prior experiences. Peter and I set up a 36 or 48-inch planet sphere model on the motion control stage. While Peter programmed a motion control ‘fly-over’ move, I quickly painted the planet white, which gave us a matte pass to later prevent the stars from double exposing.

I then painted the planet black. Then we would paint a few red, blue, and purple stripes and film the planet spinning. I painted black over those colors, put different colors over other areas, and then spun the planet at different speeds. We did multiple filmed passes with colors in different regions of the globe. So it was just a series of double exposures on a sphere with different rotational speeds.

It became a multi-exposure shot so that as the Vipers flew over, the color bands flowed around like Jupiter at different speeds.

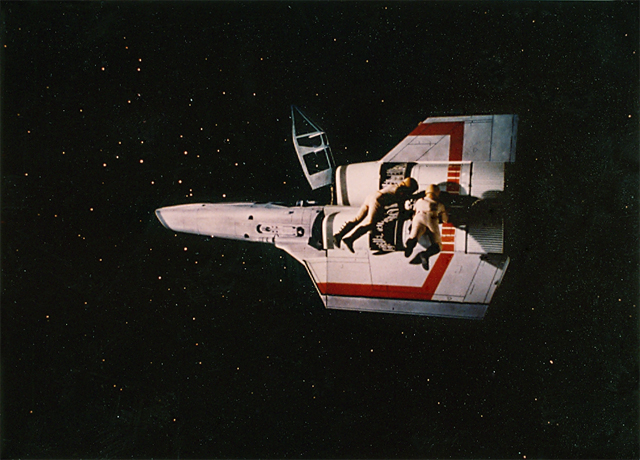

The other shot I was delighted with was where a Viper ship had been damaged. So the pilots had to do an extra-vehicular spacewalk. They’re trying to fix the side of it. So we did this long pullback, seeing these guys stranded in space.

That’s from the Galactica 1980 episode “Spaceball,” where Troy and Dillon are drifting in space for almost the entire episode and then do an EVA to repair their ship before they run out of oxygen.

Right. That was one I loved because the production had a full-size Viper and real actors, but they were unsure how to make the shot on a minimal budget. So we went to the stage, and they had some stunt guys hanging on wires in front of the full-size Viper.

So we filmed the full-size Viper and these guys hanging there as a live-action plate. Later I had a registration film print made of the live-action. I owned a rear screen, single-frame projector, so I could do rear screen projections as Ray Harryhausen did.

We also took photographs of the Viper for high-quality detail. I mounted the Viper photo on a large piece of glass. I cut out and lined up the area where the actors were in front of the real Viper, the big one. We programmed a long motion control pullback away from the Viper with these guys floating in space. I just single-framed the actor’s action frame by frame and finally added stars.

Everyone was amazed that we pulled that off without optical printing, and there were no matte lines. It was all done in the camera. Everyone was just blown away. That was one of those great shots, and I was like: “Yeah! we got that one.” That was a satisfying shot to do.

Working at Hartland was transformative. I arrived slightly intimidated and concerned because I didn’t know how to do motion control. I was still thinking, “I don’t know if I can measure up to these guys.” After some successful arcane assignments, I had a liberating awareness or pivotal experience. I finally realized what I knew. At that time, I’d already been working professionally for almost ten years, plus I’d done all that experimenting in high school and college

As it turned out, I knew a lot more than I realized. That is not a place of ego but a growth in self-awareness. It made me more confident to jump in and try more projects. I like to feel that I contributed and helped get some shots done that would not have been completed without my approach to some things. It was a pretty neat moment.

Did you also visit the sets or meet any of the actors?

I got a chance to meet Richard Hatch and Dirk Benedict. I never got the opportunity to go on the sets a lot. I got a chance to go on the Buck Rogers sets when they were shooting some of their crazy episodes, but for the most part, we were pretty insulated. It wasn’t like Star Trek, where I was frequently on the set.

I was one of the VFX crew; David Garber and Wayne Smith were the effects supervisors in charge of the VFX and ran the Hartland facility. Peter Anderson was the on-set supervisor and was responsible for how all the effects shooting worked. So I was under him and kind of low on the food chain.

How much freedom were you given to realize the effects?

Peter Anderson was a great guy to work with. Once he realized what I could do, he gave me a lot of freedom. Peter was very supportive of all the guys and me. He gave people as much independence as needed to get the jobs done. Let’s face it: we had to turn in a lot of work quickly, and if you’re being micromanaged and everything is looked at repeatedly, you’d never get anything done. So basically, they had a lot of really good people who knew what they were doing, and there were very few snafus in the process, believe it or not. At the time, I was pretty insulated from most of the staff. I knew what I needed to do, we all had meetings, and we all talked about what had to happen. Then, you go and do it. We had ridiculously long hours, but it was a delightful and wonderful studio to work at.

Peter Anderson circa 1979

Peter was also — you may or may not hear this from anybody else — a bit of a jokester. He knew it was stressful, so he would sometimes bring food in, but if Peter ever walked out with his rain slickers, you knew you were in trouble. He had a set of rain tans and overcoats, stuff like that, for rain and wet stuff, because he loved to pie people — hit them with pies or food fights, things like that. It blew off a lot of tension, plus we all got a certain level of camaraderie from all that silliness. It wasn’t done at certain times. It didn’t hurt the production or anything like that. We finished a shot or got some accomplishment, and he’d bring in some food. It was always exciting and often ended with the famous Peter Anderson Hartland food fights. Those were the only times these guys were silly and zany. Otherwise, they were an exceptionally professional group working their butts off.

Especially at the end of the pilot, when there was a lot of time pressure, was there also some original equipment made by the ILM crew, reused to create new things?

Of course, all the models and some crew came over. I think Colin and Gil Cantwell were part of that group, along with Davy Jones, Pete Gerard, and some of the model guys.

When I got there, Hartland was running and flowing pretty well. Hartland engineers were still building equipment — I know that – because Richard Bennett and Gil Cantwell were building these incredible machines, which were patterned after something Richard Edlund had put together for John Dykstra at ILM. I heard an interview where Richard Edlund shared that he was displeased that some of his equipment was copied at Hartland. I don’t know what was copied, but it was basic mechanical construction.

Richard Edlund circa 1977-78

The production needed a repeatable camera platform that had to go up and down, pan and tilt, and be on a track. You can build a big Dykstraflex boom arm at considerable costs or use an existing dolly and get it up and running, so you can start making movies. Taking the expedient route allowed Hartland to get some stuff done pretty quickly.

I heard the flying motorcycles were actually built for an episode of Battlestar Galactica, which wasn’t filmed, and they later reused those for Galactica 1980.

Oh, were they? Was that what happened? Galactica 1980 had sort of the same problems that V did. You’re spending a lot of money on getting the show set up, but you can’t keep on spending the money, and you go: “Those spaceships can’t keep flying around. Let’s go and have them ride motorcycles.” Later, V: the Series did a similar motorcycle budget saver. When you’re cutting costs, you sometimes get crazy solutions.

Alan Levi, who took over from Richard Colla on the pilot, said there was a set budget for the season in those days. Most of the money was always spent on the first five episodes to get the audience to watch it, but all the money spent only led to cheaper shots in the later episodes.

Sure, that’s right. We saw that happening. The shot count started going down, and the editors began recycling stuff. There was one episode — Gosh, it was in Buck Rogers, I think – there was a sequence where our heroes had to go from one place to another. In one shot, it’s Princess Ardala’s shuttle, and in another shot, in the same sequence, it’s the Battlestar Galactica shuttle. I was saying, “Oh my God, guys!” They responded, “Don’t worry; nobody will notice.” Well, everybody noticed! It looked horrible.

I don’t remember if it was the Hawk ship, but some spaceship is going into a cave, and you see its blazing engines as it goes in. Later there’s a shot of it coming out of the cave, and they just optically printed it backward, so now it’s flying out with its engines blazing backward. They were so desperate for money that they were doing crazy stuff like that toward the end of production. I was rolling my eyes, “Oh my God!”

Eventually, I learned not to take things personally. It’s not my show. I need to be responsible for my shots and do my best. If the producers, directors, or somebody else wants to drop or change something, that’s out of my control — it’s not my movie. I groaned about some clunky work there, but I can also say that about other productions.

How surprised were you that they restarted Battlestar Galactica only a year after it had been canceled?

Oh yeah, we all were surprised but glad to work on it.

Were the lower budgets for Galactica 1980 also affecting your work and your co-workers in the visual effects department?

Dan Curry circa 1980

I don’t remember being adversely affected by that, except we had very little time. For example, in Galactica 1980, the flying saucer hangar matte shot was done in one week. That’s all the time we had. Matte artist Dan Curry and I had to go to the studio, shoot the plate, come back, paint the thing, and put it together. It was finished in seven insane days.

Some of the stuff was just crazy — little tiny things we had to do. I was filming elements on the down shooter. I did this little matte shot that was 2 ½ inches wide of a building in the distance. I think it’s in the show. It’s some refinery or factory, and it’s off in the distance. It’s just some little front and backlight thing, and I jumped in and did it. When you don’t have much money, you do what you can. It just comes with the territory. You just suck it up and do it.

I had a great time because I always had something to push my mind against. Maybe that’s one advantage I had over some folks who don’t remember doing this stuff that well. I was very young when I was doing it, and everything was a big memorable challenge to work on. I was trying to figure out how to do them and what was the best way and coming up with solutions that we could do within the time frame. So, I don’t remember talking about money per se. I know the budgets were tight. We couldn’t do some things because we didn’t have enough time to do them well or we didn’t have enough resources to make them happen at all.

But sometimes there was something spectacular that we got to do. That attack on Earth, the Cylons coming on straight down Hollywood Boulevard, was one of those things I got a chance to work on.

I’ve also read that some of the towers on fire in those shots are from other movies.

Yes, stock shots. We used stock shots all the time. Why not? We tried to do an awful lot with very little money on that Hollywood Blvd. sequence. One Galactica 1980 shot you may or may not hear about from anybody else is what happened with a bunch of extras…

We were on the Universal backlot. I was the matte cameraman filming the scene so Jena Holman could paint in the Hollywood sign and hills in the distance. Because the scene called for the Cylon Raiders to be strafing Hollywood Blvd., the Special Effects Dept set long rows of charges or squibs down the street.

The extras were told to show up to set in street clothes, and one lady wore a large bright yellow hat. The Assistant Directors (ADs) grouped the extras on each street corner. The extras are told that the Cylons are attacking and to run across the street screaming. The yellow-hat lady stood out brightly. Unfortunately, they didn’t have enough extras, so for more screen time, one AD would run people across the street, and the other assistant director would turn them around and run them back. That should have worked, except for the very obvious yellow-hat lady running back and forth screaming.

The extras were all running back and forth, screaming at nothing because they couldn’t see Cylon Raiders strafing or anything unusual around them. Yet.

But, then, down the center of the street, these long strips of strafing sparks suddenly go off sequentially and zoom down the road toward and right under this crowd.

So now the extras were really panicking, wildly running and leaping as explosives went off under them and between their legs. We all watched with our mouths hanging open. Of course, nobody got hurt, but it was one of those scenes that was way more startling than dangerous. Ultimately this shot was cut from the sequence, but we got a good “war story” to tell, even the lady in the large yellow hat.

All photographs are (c) copyrighted by their respective owners and are used for educational purposes.

Recent Comments